Investigating Residual Stress in Rock Using Micromechanical Modelling in RS2

Residual stress, meaning the locked-in microstresses within rock formations, hasn’t been widely explored in recent rock engineering research. However, these stresses could be a missing piece in understanding crack behavior, excavation stability, and in situ stress measurements. Ignoring them in your models can lead to underestimations of deformation and failure risks.

New research used RS2’s micromechanical modelling tools to model residual stress effects in rock. Researchers simulated residual stress fields and analyzed their impact on compression-induced crack closure, stress redistribution, and excavation stability. Their findings make a strong case for integrating residual stress into geotechnical analysis. Here, we’ll share the highlights on how RS2 contributed to the project, and for the full story and relevant figures, read the original research paper by M. Trzop and A.G. Corkum.

The Geological Setting

Residual stress in rock can form through geological processes like magma cooling, recrystallization, and cementation under stress. Unlike engineered materials such as glass and metal, where residual stresses are more thoroughly researched and used for strength improvements, rock formations exhibit highly heterogeneous stress distributions due to their complex mineralogy and history. These stresses can persist for millions of years.

Despite its role in material behavior, residual stress has been largely overlooked in geotechnical engineering models, partly due to the challenges of measuring and numerically representing its complex formation.

The Research Challenge

Traditional rock mechanics models assume that stress conditions are dictated by external loads, but this neglects pre-existing residual stress fields. This gap in modelling presents multiple challenges.

Residual stress influences crack behavior in ways conventional models may not capture. In compression tests, cracks often close before peak stress is reached, yet predefined cracks are required in current models to simulate this effect. Additionally, stress redistribution during excavation or coring can contribute to unexpected fracturing, affecting rock stability and mechanical properties.

The Solution

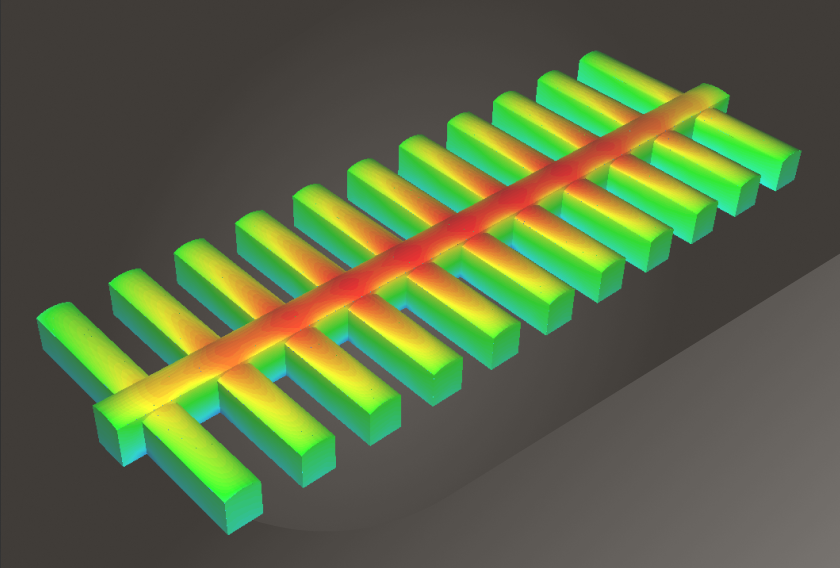

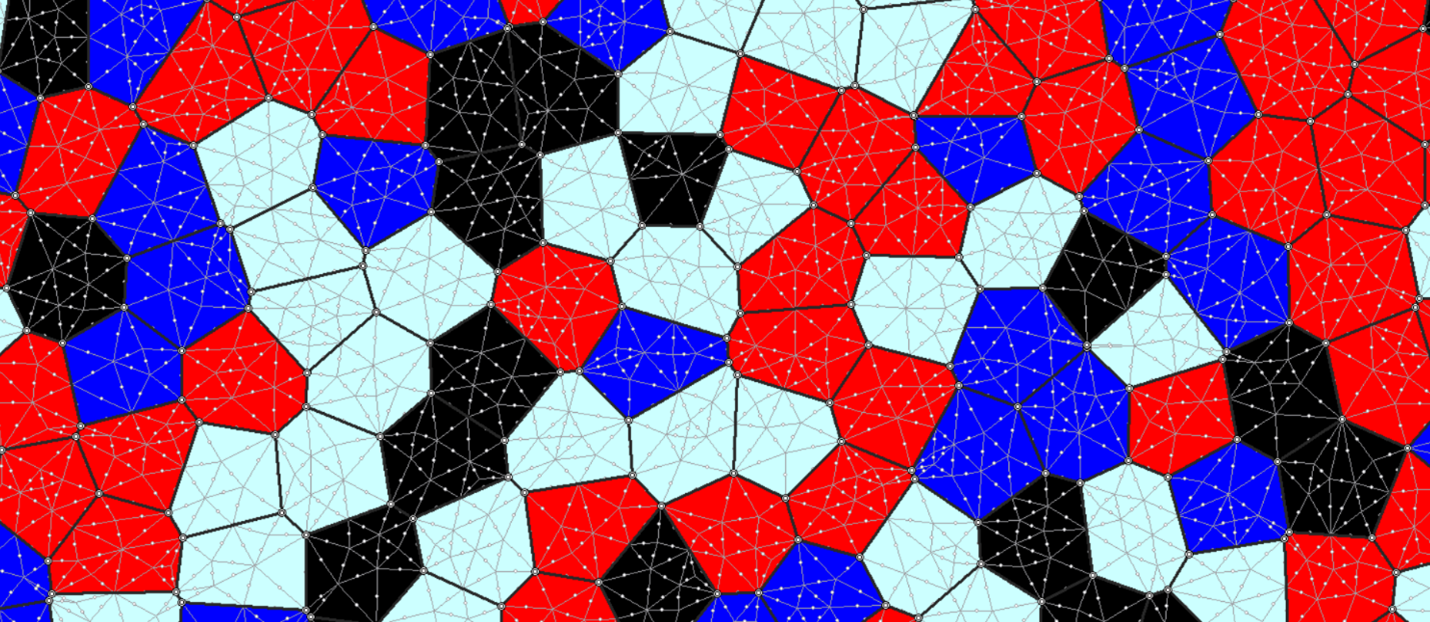

The research team used RS2 to investigate residual stress effects by creating micromechanical models based on Voronoi grain-based structures, which provided a more accurate representation of rock microstructure.

In the research, residual stress was introduced by adjusting Young’s modulus in staged simulations, mimicking natural rock hardening to create a self-equilibrating stress field.

The key modelling scenarios researchers explored are:

- Crack closure in compression tests: Where they examined how residual stress affects early-stage stress-strain behavior.

- Microcrack formation and propagation: Where they assessed whether residual stress redistribution creates new cracks or extends existing ones.

- Slot cut propagation under tension: Where they investigated whether residual stress alters crack growth rates.

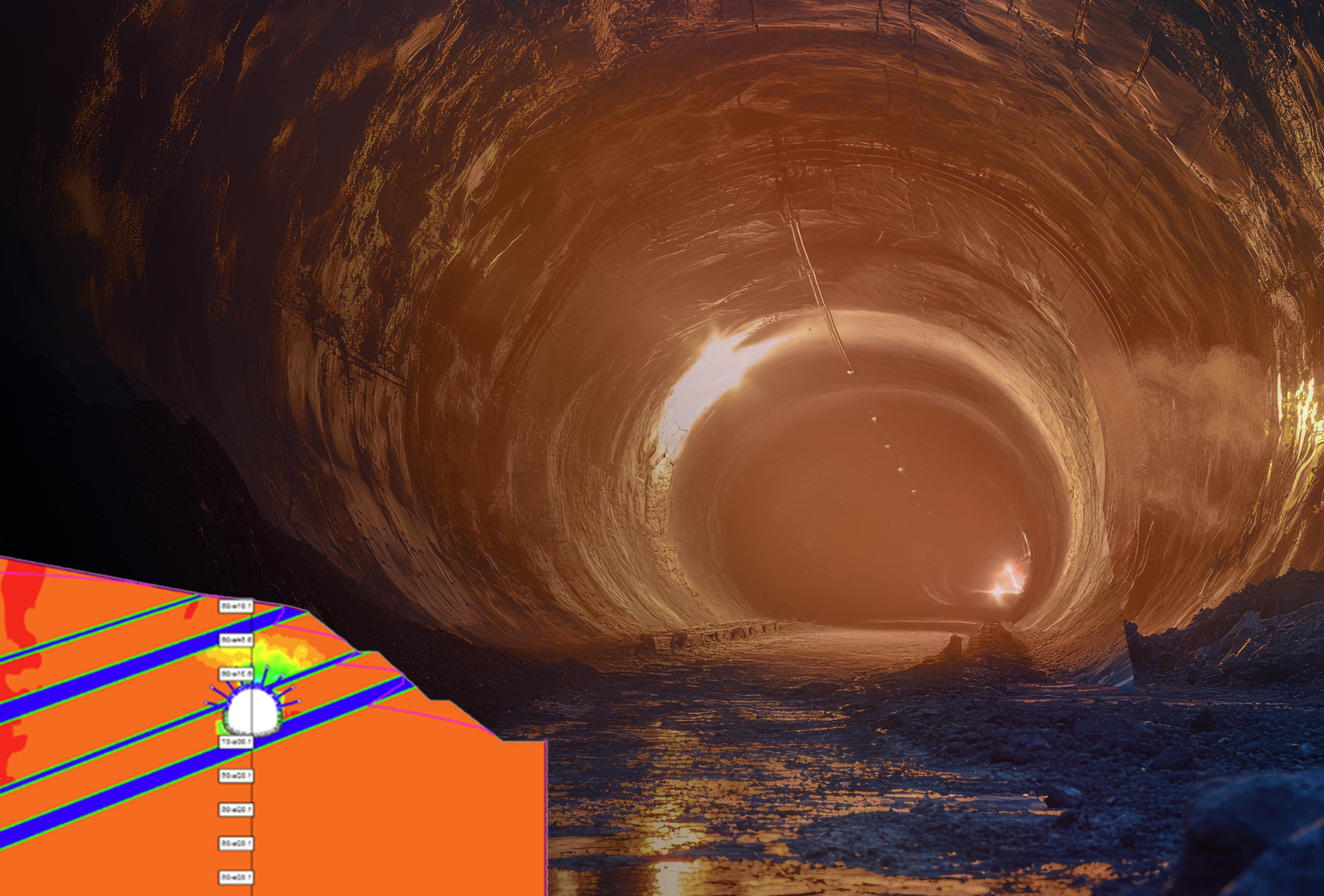

- Excavation-induced deformation: Where they evaluated how residual stress mobilization affects tunnel stability and borehole stress redistributions.

These simulations aimed to determine whether residual stresses significantly impact rock behavior and whether their exclusion from engineering models could lead to inaccurate predictions.

The Results

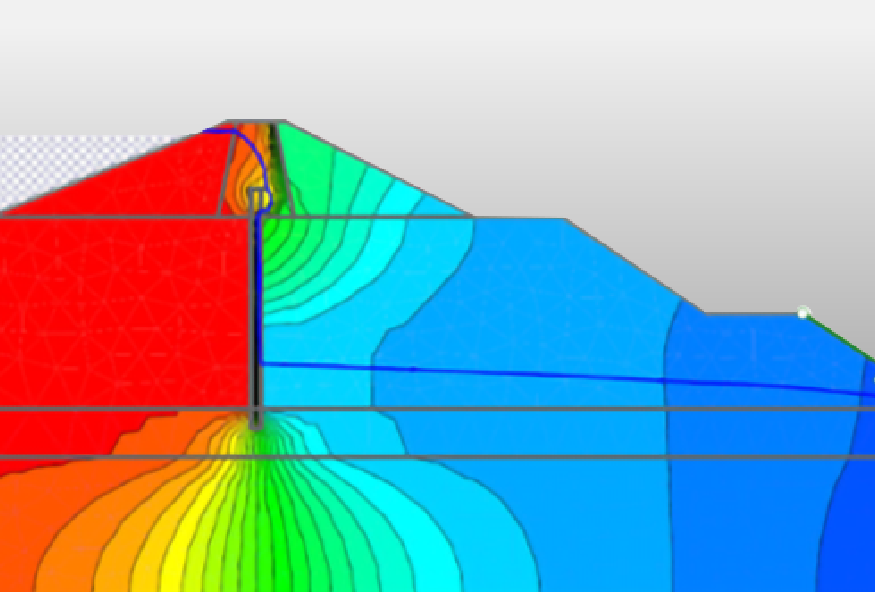

RS2 simulations confirmed that residual stress has a measurable impact on rock mechanics. In compression tests, models with residual stress exhibited greater crack closure strains, revealing that microcracks remain open even before external loading. Figures 7, 8, and 9 in the original research paper illustrate how these stress-strain relationships challenge conventional modelling assumptions, where predefined cracks are typically required to replicate observed behavior.

Stress redistribution due to residual stress led to new microcrack formation and propagation, particularly in tensile zones, while compressive residual stress delayed crack growth (Figures 10, 11, 12, and 13). Excavation models also revealed that ignoring residual stress results in underestimated deformation near tunnel boundaries, affecting support system design (Figures 17 and 18). Changes in displacement patterns due to residual stress under in situ conditions are visualized in Figures 19 and 20.

In situ stress measurements were also distorted by residual stress. Standard overcoring techniques assume stress redistribution occurs solely due to external loads, but RS2 models showed that residual stress can alter readings. Figure 21 highlights how tensile residual stress may open microcracks, leading to potential misinterpretations of site conditions.

The Verdict

Residual stress has real and measurable impacts on rock behavior. Ignoring it in engineering models could lead to:

- Misinterpreted stress-strain data.

- Unexpected crack propagation.

- Underestimated excavation displacements.

- Inaccurate in situ stress measurements.

With RS2, researchers could simulate these effects and gain a clearer understanding of how residual stress can shape rock behavior. By incorporating residual stress into modelling workflows, engineers can improve excavation designs, refine stress measurement techniques, and build more reliable geotechnical models.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is residual stress in rock, and why is it important in geotechnical engineering?

Residual stress in rock refers to locked-in stresses that exist without external loads, formed through geological processes like crystallization, metamorphism, and long-term stress changes. Unlike applied stresses, these internal forces influence how rock behaves under excavation and loading.

For geotechnical engineers specifically, residual stress can impact stability, deformation, and failure patterns. Ignoring it can lead to inaccurate predictions in rock mass behavior, affecting excavation safety, tunnel stability, and in situ stress measurements. By recognizing its role, you can better refine models and improve design decisions.

How does residual stress influence the mechanical behavior of rock?

Residual stress alters how rock deforms, fractures, and distributes loads. It can hold microcracks open or compress grain boundaries, making the rock seem stronger or weaker than it is.

In engineering applications, residual stress affects crack propagation, deformation near excavations, and in situ stress readings. Overlooking it can lead to unexpected failures or misinterpretations of a rock’s true strength. Including residual stress in analysis ensures more reliable stability assessments.

What are the most common residual stress measurement techniques used in rock mechanics?

Residual stress is measured using X-ray diffraction (XRD), overcoring, hole drilling, and strain relief techniques. These methods detect stress by observing how rock deforms when material is removed or by analyzing crystal structures.

XRD provides precise micro-scale data but is limited to surface analysis. Overcoring and hole drilling allow for in situ measurements but require careful execution to avoid errors. Engineers often use a combination of these methods for a more complete picture.

How do X-ray diffraction (XRD) and overcoring methods measure residual stress in rock?

XRD detects residual stress by analyzing shifts in atomic spacing within mineral grains. When stress is present, diffraction angles change, revealing strain within the rock. This method is precise but limited to surface-level analysis.

Overcoring involves drilling around a strain-gauged rock sample. As stress is relieved, the gauges record how the rock relaxes, allowing engineers to back-calculate the original stress state. It’s effective for larger-scale measurements but requires precise calibration.

How does the hole drilling residual stress method work for rock materials?

Hole drilling measures residual stress by removing a small section of rock and tracking how the surrounding material deforms. Strain gauges placed around the hole record these changes, allowing engineers to calculate the original stress field.

This method works well in metals and concrete but is trickier in rock due to its natural heterogeneity. Drilling can introduce microcracks, slightly altering results, but it remains a useful technique for localized stress assessments.

What is crack density, and how is it measured in rock mechanics?

Crack density refers to the number and distribution of microcracks within a rock, influencing its strength, permeability, and failure behavior. Higher crack density means lower strength and greater deformation potential.

It’s measured using thin-section microscopy, image analysis, or digital fracture mapping. Engineers also infer crack density from stress-strain behavior in lab tests or simulations, helping refine stability assessments and excavation models.

What does rock sample compression testing reveal about residual stress?

Compression testing helps engineers understand a rock’s strength and stiffness, but residual stress can distort results. Internal tensile stress may keep microcracks open, affecting deformation patterns under load.

Residual stress can cause an initial “closure phase” in stress-strain curves, where cracks close before true elastic deformation begins. Recognizing this effect helps ensure accurate strength assessments in geotechnical design.

How does micromechanical modelling of rocks help in understanding residual stress?

Micromechanical modelling simulates grain interactions and crack propagation, providing insight into how residual stress influences rock behavior. These models help visualize stress redistribution and failure mechanisms that are hard to capture in lab tests.

By replicating stress conditions at the micro-scale, engineers can better predict excavation stability and deformation. This approach is particularly useful for studying stress-related fracture behavior and refining stability models.

What are the benefits of using RS2 for micromechanical modelling of residual stress in rock?

RS2 provides a robust platform for simulating residual stress effects in rock. Its continuum-based micromechanical modelling captures stress redistribution, crack behavior, and deformation patterns that traditional models often miss.

By incorporating residual stress, RS2 improves accuracy in excavation design, stability analysis, and failure prediction. Its ability to model crack closure and stress redistribution makes it a valuable tool for engineers working in complex geotechnical environments.